Use

Different types for different needs

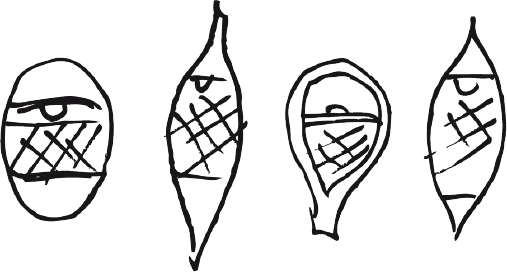

Various types of snowshoes are used, depending on snow quality and the area they are used in. The same nation may use a number of different models.

Uikutshieu asham [innu]

In the spring and fall, when there are patches of bare soil, snowshoes laced with fishing line are used. They are much easier to repair because fishing line is much more flexible than babiche. These are temporary, bearpaw-shaped snowshoes.

Mashk asham [innu] – Bearpaws

The Innu used bearpaw snowshoes for working. The width of the snowshoe depends on the environment. The Innu who live along the St. Lawrence River where the forest is denser preferred narrower snowshoes that make it easier to walk through the bush.

Bearpaw snowshoes were also used by children, because they outgrew them quickly, and they are easier to make.

Beavertail snowshoes

This type of snowshoe is made for walking. They float on the snow better than any other type of snowshoe. Their shape provides better stability and prevents snow from being thrown onto the backs of the legs.

In the woods, when a moose or other large game animal was killed, the hunters would return to camp to get their beavertail snowshoes, which allowed them to carry more weight.

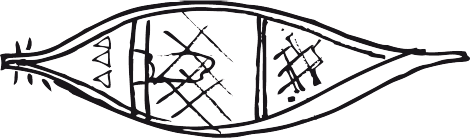

Curved tip snowshoes

Snowshoes with curved tips were used for travelling. You can run with these snowshoes because they are longer and lighter than the other types.

Huron snowshoes

These snowshoes, also called common snowshoes, were used on a daily basis for hunting, trapping, and working around the tent.

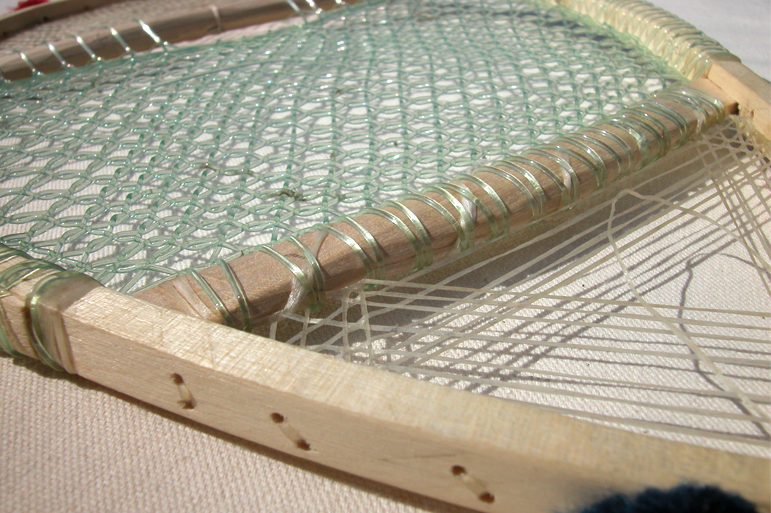

1. Uikutshieu asham – Intermediate snowshoes

Alexandre Pinette, Innu

Wood, nylon wire, sinew, wool

La Boîte Rouge vif archives, 2005

2. Temporary snowshoes

Alexandre Pinette, Innu

Wood, nylon rope

Archives de La Boîte Rouge vif, 2005

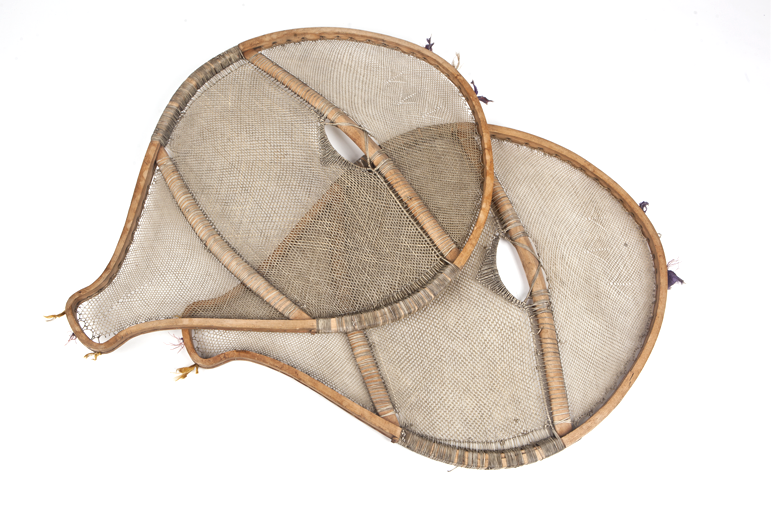

3. The common snowshoes

Mina Pissinicouane

Eeyou, Chisasibi

White spruce, sinew

Les Musées de la civilisation, 66-462

Photograph : Jessy Bernier – Perspective

4. Mashk asham – The Bearpaws

Innu, Côte-Nord

Wood, sinew

Les Musées de la civilisation, restored by Centre de conservation du Québec, 68-3075

Photograph : Jessy Bernier – Perspective

5. Curved tip snowshoes

Georges Pepabano

Eeyou, Chisasibi

Birch, paint, fiber, wool

Les Musées de la civilisation, 75-987

Photograph : Jessy Bernier – Perspective

6. Beavertail snowshoes

Johnny and Emma Shecapio

Eeyou, Mistissini

Wood, fiber, wool, sinew

Les Musées de la civilisation, 83-2235

Photograph : Jessy Bernier – Perspective

When coming out of a tipi on snowshoes, one snowshoe should point east and the other west. The purpose of this is to ask the spirits to help you find your way and return safely to camp.

When coming out of a tipi on snowshoes, one snowshoe should point east and the other west. The purpose of this is to ask the spirits to help you find your way and return safely to camp.

Elders sing to ask for assistance from the spirits while they make snowshoes. Women help their husbands and do the lacing.

Elders sing to ask for assistance from the spirits while they make snowshoes. Women help their husbands and do the lacing.

Traditional activities are based on six seasons. Snowshoe-related activities mainly occur in the first and the second season. In September and October, Eeyou (Cree) travel to their respective trap lines and hunters kill moose, bear, and smaller game. Cree women prepare and dry moose hide. The skins are immersed in water again to extract the babiche for snowshoe webbing. The second season is in November and December. Hunters make traditional tools to assist them in their trapping endeavours while waiting for rivers and lakes to freeze before they can start hunting again. It's at this time of year that they make snowshoes for their families.

Traditional activities are based on six seasons. Snowshoe-related activities mainly occur in the first and the second season. In September and October, Eeyou (Cree) travel to their respective trap lines and hunters kill moose, bear, and smaller game. Cree women prepare and dry moose hide. The skins are immersed in water again to extract the babiche for snowshoe webbing. The second season is in November and December. Hunters make traditional tools to assist them in their trapping endeavours while waiting for rivers and lakes to freeze before they can start hunting again. It's at this time of year that they make snowshoes for their families.